ABOUT THIS BOOKLET

This booklet is for anyone who has an increased risk of developing breast cancer.

This includes people who have inherited an altered gene that increases their risk.

It’s also relevant for people who have been diagnosed with breast cancer and remain at higher risk because of their family history.

The booklet explains the different options that might be available to you for managing your risk.

It also covers topics such as talking to your family about being at increased risk and worries about passing on an altered gene.

CANCER RISK AND ALTERED GENES

Some people have a higher risk of developing breast cancer and possibly other cancers because they have inherited an altered gene.

Genetic testing is used to find out whether an altered gene runs in the family.

An altered gene may also be referred to as a gene change, fault, variant or mutation.

BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2 and other altered genes

The most common inherited altered genes that increase the risk of breast cancer are called BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA stands for BReast CAncer).

BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes usually protect us from developing breast and ovarian cancer. However, inheriting an alteration in one of these genes increases the risk of developing cancer.

Other less common altered genes may also increase the risk.

How altered genes affect cancer risk

A person with an altered gene is sometimes referred to as a gene carrier.

Being a gene carrier does not mean you will develop breast cancer, ovarian cancer or related cancers.

However, you will have a higher risk than the general population.

General population

During their lifetime, women have a:

- 15% risk of breast cancer

- 2% risk of ovarian cancer

BRCA1

Women with an altered BRCA1 gene have a:

- 60–90% risk of breast cancer

- 40–60% risk of ovarian cancer

Men with an altered BRCA1 gene have a 0.1–1% risk of breast cancer.

BRCA2

Women with an altered BRCA2 gene have a:

- 45–85% risk of breast cancer

- 10–30% risk of ovarian cancer

Men with an altered BRCA2 gene have a 5–10% risk of breast cancer, and up to 25% risk of prostate cancer.

Less common altered genes

PALB2

Women with an altered PALB2 gene have a 44–63% risk of breast cancer.

TP53

Women with an altered TP53 gene have an up to 85% risk of breast cancer.

The lifetime risk for a person with an altered TP53 gene to develop any type of cancer is 90%.

CHEK2

Women with an altered CHEK2 gene have a moderate risk of developing breast cancer.

Moderate risk is higher than the general population. However, it’s still more likely they will not get breast cancer.

ATM

Women with an altered ATM gene have a moderate risk of developing breast cancer.

Moderate risk is higher than the general population. However, it’s still more likely they will not get breast cancer.

Other genes

Some genetic conditions caused by rare altered genes are also associated with breast cancer.

These include:

- Peutz-Jegher syndrome (altered STK11 gene)

- Cowden syndrome/PTEN hamartoma tumour syndrome (altered PTEN gene)

- Hereditary diffuse gastric (stomach) cancer syndrome (altered E-cadherin (CDH1) gene)

- Neurofibromatosis type 1 (altered NF1 gene)

If one of these runs in your family, your genetics team will talk to you about your risk of breast cancer.

MANAGING YOUR RISK

There are several options available to help you manage your risk of breast cancer.

These include:

- Regular breast screening

- Drug treatments

- Risk-reducing surgery

The following sections look at these options in more detail.

Genetic counselling

All cancer genetics clinics have specialist teams who you can talk to about how you’re feeling.

Following genetic testing you’ll be offered an appointment with a genetic counsellor (a healthcare professional

with specialist knowledge about genetics and inherited illnesses) or a clinical geneticist (a doctor with specialist training in genetics).

You may be offered an appointment where you’ll meet different members of the multidisciplinary team who specialise in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer.

This may include a breast surgeon, plastic surgeon, gynaecologist, oncologist, nurse specialist, research nurse and clinical psychologist.

They can help you understand more about your risk of developing breast cancer and other cancers and the options that may be available to help manage your risk.

This may be done as one visit or over several visits.

For some people it can be a very emotional time. You may feel anxious talking about your risk and what this means for those around you.

Your genetics team will be experienced in talking through the issues involved and will be able to offer you support if you need it.

BREAST SCREENING FOR PEOPLE AT INCREASED RISK

If you have been assessed as being at moderate or high risk of developing breast cancer, you’ll be offered regular scans to check for breast cancer, depending on your age. This is known as screening or surveillance.

The aim of screening is not to reduce your risk of breast cancer but to pick up breast cancer early, before there are any obvious signs or symptoms.

The sooner breast cancer is diagnosed, the more successful treatment is likely to be.

Your genetics team will arrange your screening and will refer you to a local NHS breast screening programme.

What does screening involve?

Screening may include a mammogram (a breast x-ray) or an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan. An MRI uses magnetic fields and radio waves to produce a series of images of the inside of the breast.

The type of screening you’re offered will depend on:

- Your age

- Whether you have had breast cancer

- Your level of risk

Younger women are not usually offered mammograms. This is because they’re more likely to have dense breast tissue, which can make mammogram images less clear.

If you’re at high risk, the type of screening will also depend on your individual likelihood of being a gene carrier.

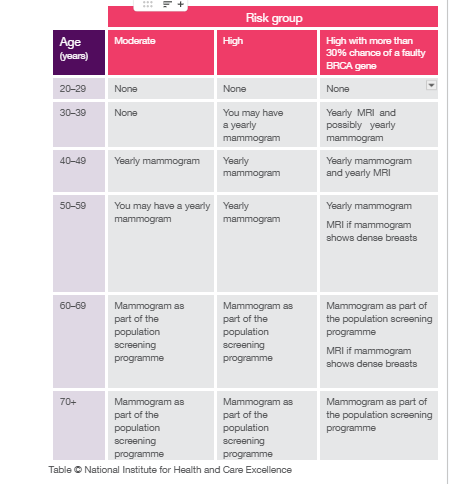

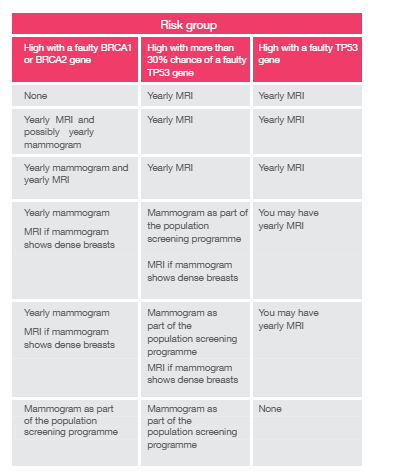

Breast screening recommendations

Your breast screening recommendations will be based on national guidance.

- England and Wales follow the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) – Familial breast cancer clinical guideline (CG164)

- Scotland follows the Health Improvement Scotland – Familial breast cancer report

- Northern Ireland follows the Health and Social Care (HSC) – Higher risk surveillance programme

Information about screening

Your genetics team should give you information about the possible advantages and disadvantages of screening.

Whether you go for screening is your choice. It’s important you have the information you need to make your decision.

You can also read more about screening in our booklet Know your breasts: a guide to breast awareness and screening.

NICE screening recommendations for women who have not had breast cancer

A small number of women at very high risk will be offered screening before the age of 30. Your specialist genetics team will assess your individual risk and refer you to the NHS breast screening programme for regular MRI scans if you’re eligible.

National (population) breast screening programmes

Once your increased screening stops, you’ll usually be transferred onto a national (sometimes called population) breast screening programme.

If you’re under 70 you’ll be invited for a routine mammogram every three years.

After the age of 70 you can still have a mammogram every three years, but you’ll have to contact your local breast screening unit to get an appointment.

Is there screening for ovarian cancer?

There’s currently no NHS screening programme for ovarian cancer. This is because there isn’t an effective way of detecting ovarian cancer at an early stage.

However, ongoing research is looking at ways of screening for ovarian cancer. Your specialist team will talk to you about any trials that may be suitable for you.

NICE screening recommendations for women who have had breast cancer

If you have had breast cancer, you’ll have increased screening for five years or longer depending on your age as part of your follow-up care.

Once your follow-up period ends, if you’re at moderate risk you’ll have the same screening recommendations as women at moderate risk who have not had breast cancer (see table).

If you remain at high risk of developing another breast cancer or are a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene carrier, you should be offered:

- Yearly MRI scans (alongside a mammogram) if you’re aged 30–49

- Yearly mammograms if you’re 50–69

If you’re over 70 and your follow-up period has ended, you can still ask for a mammogram every three years as part of a national breast screening programme.

If you have an altered TP53 gene, you will not be offered mammograms, but you may be offered yearly MRI scans between the ages of 20 and 69.

TREATMENT TO REDUCE THE RISK OF BREAST CANCER

If you’re at moderate or high risk, your specialist team should talk to you about the possibility of treatment options to reduce your risk.

You should be told about all the possible risks and benefits of these treatments, and by how much they may reduce your risk of developing breast cancer.

Why are men with an altered gene not offered screening or treatment?

Men are not offered breast screening or risk-reducing treatment, even if they are gene carriers. This is because their overall risk of breast cancer is lower than women in the general population.

It’s important for men to check their chest area regularly and to know what looks and feels normal for them.

DRUG TREATMENT TO REDUCE THE RISK OF BREAST CANCER

The drugs tamoxifen, anastrozole and raloxifene are available in the NHS for some women with an increased risk of developing breast cancer.

Taking medication to reduce the risk of breast cancer is known as chemoprevention. Despite the name, these drug treatments are different from chemotherapy, which is used to treat cancer.

Research has shown that taking tamoxifen, anastrozole or raloxifene for five years can help reduce the risk of developing breast cancer in women at moderate or high risk due to their family history.

However, the evidence remains uncertain for gene carriers. Current evidence suggests while drug treatment may benefit BRCA2 gene carriers, the benefit for BRCA1 gene carriers is less clear.

Who might be offered drug treatment?

If you’re at high risk, over 35 and have not been through the menopause (pre-menopausal), your genetics team may recommend you take tamoxifen for five years. Tamoxifen may also be considered if you are pre-menopausal and at moderate risk.

If you’re at high risk and post-menopausal, your genetics team may recommend anastrozole, tamoxifen or raloxifene for five years. This may also be considered if you are post-menopausal and at moderate risk.

Women who have an altered gene may be offered drug treatment, depending on the type of gene.

If you decide to take drug treatment, you’ll still be offered regular screening (see page 6).

You will not be offered drug treatment if you have already had risk-reducing surgery (see page 16).

Deciding whether to have drug treatment

Your genetics team will talk to you about the possible benefits and side effects of drug treatment.

They’ll also tell you by how much the drugs may reduce your chances of developing breast cancer. This will depend on your individual situation.

NICE has produced decision aids for both pre- and post- menopausal women who may be considering drug treatment to reduce their risk of developing breast cancer (see page 35).

Side effects

Like all drugs, tamoxifen, anastrozole and raloxifene can cause side effects.

Tamoxifen and anastrozole commonly cause menopausal symptoms. These include hot flushes and night sweats, vaginal dryness, reduced sex drive and mood changes. These symptoms are often more intense than when the menopause happens naturally.

Raloxifene can cause side effects such as hot flushes and sweats, and flu-like symptoms.

Tamoxifen and raloxifene increase the risk of blood clots, such as a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). If you have a history of blood clots, you may not be able to take these drugs.

You should not take tamoxifen or raloxifene if you’re pregnant or planning to start a family as the drugs may be harmful to a developing baby.

Our booklets Tamoxifen and Anastrozole (Arimidex) have more information about these drugs and their possible side effects.

If you have had or are having treatment for breast cancer

Anyone who has had breast cancer has a slightly higher risk of developing a new primary breast cancer. Your family history may increase this risk further.

A new primary breast cancer is when a new breast cancer develops. It’s not the original cancer coming back (known as recurrence).

If your family history puts you at moderate or high risk, you’ll continue to have increased screening after your follow-up period ends (see page 8).

If you had genetic testing during your cancer treatment and were found to be a gene carrier, your treatment

team may discuss additional surgery to reduce the risk of developing a new breast cancer. This may be offered at the same time as the surgery to treat your breast cancer.

Having an altered BRCA gene may also affect the cancer treatments you’re offered.

If you have genetic testing after finishing treatment for breast cancer, your genetics or breast team may talk to you about your individual risk of recurrence when discussing options for managing your genetic risk.

Your treatment team will talk through your options and support you with your decision. Your genetics team may also arrange for you to see a gynaecologist to discuss surgery to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer (see page 24).

RISK-REDUCING SURGERY

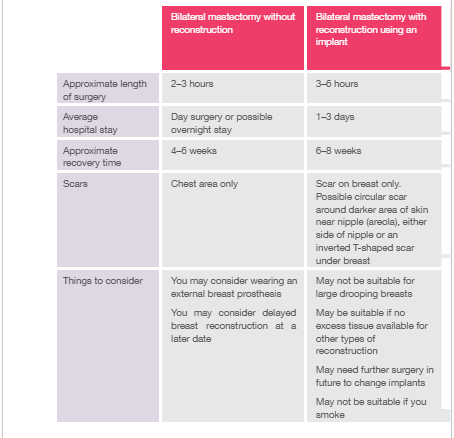

Risk-reducing surgery involves removing the breast tissue from both breasts. This type of surgery is called a bilateral mastectomy.

A bilateral mastectomy can significantly reduce the risk of developing breast cancer by 90–95%, but it cannot completely remove the risk. This is because it’s not possible to remove all the breast tissue during a mastectomy.

Who might be offered risk-reducing surgery?

Your specialist team should discuss the possibility of surgery if you’re at high risk of developing breast cancer, or you are a BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2 or TP53 gene carrier.

Risk-reducing surgery is also an option for women who have had breast cancer and are at high risk of developing another breast cancer.

Surgery may be discussed with some women who have an altered CHEK2 or ATM gene, depending on their family history.

What does risk-reducing surgery involve?

The two main types of risk-reducing surgery are:

- Removal of both breasts including the nipples (a bilateral mastectomy)

- Removal of both breasts but leaving the nipples intact (a nipple-sparing mastectomy)

Breast reconstruction

Breast reconstruction is surgery to create a new breast shape after mastectomy.

Breast reconstruction is usually offered at the time of your risk- reducing surgery. This is known as immediate reconstruction.

The three main options are reconstruction using:

- Your own tissue taken from another part of the body (the most common area being the lower part of the abdomen)

- A breast implant

- A combination of tissue and an implant You may be offered more than one option.

Your breast team should discuss with you all the possible risks and benefits of having risk-reducing surgery. They may explain why they think a particular breast reconstruction option is best for you.

Some women may be advised not to have a breast reconstruction or to consider a delayed reconstruction because of other medical conditions or lifestyle factors that may increase the risk of complications after surgery.

Some women choose not to have reconstruction and prefer to wear an external breast form (prosthesis) or choose to ‘live flat’ and don’t have a reconstruction or use a prostheses.

Comparing types of surgery

Nipple preservation

Your breast team may discuss the option of keeping your nipples. This is known as nipple preservation or a nipple- sparing mastectomy.

This operation involves removing all the breast tissue while leaving behind the nipples.

Your breast team will discuss the risks and benefits of nipple preservation, including loss of sensation and

function of the nipple, and let you know if it’s an option for you.

People often choose to keep their nipples for visual reasons.

If nipple preservation is not an option or you decide you do not want to keep your nipples, your breast team will let you know what options are available after your risk- reducing surgery and breast reconstruction. These may include nipple reconstruction, and nipple and areola tattooing (the areola is the darker area of skin around the nipple).

Some women use stick-on nipples (a nipple prosthesis). These can be custom made, sometimes by the hospital, or bought ready made.

Some women choose not to have a nipple on their reconstructed breast.

You can find out more about nipple reconstruction and tattooing in our Breast reconstruction booklet.

Deciding whether to have risk-reducing surgery

Choosing whether to have risk-reducing surgery is a complex and personal decision.

There’s no right or wrong choice and it’s important to do what you feel is best for you.

There are lots of things to consider, including the type of surgery to have and the timing of your surgery.

It can help to talk to other women who have faced a similar decision.

Breast Cancer Now can put you in touch with someone who has had risk-reducing surgery or the type of breast reconstruction you’re considering through our Someone Like Me service.

Call our Helpline 0808 800 6000 or visit breastcancernow.org for more information.

For information about breast reconstruction, see our Breast reconstruction booklet. For information on breast prostheses, you can read our booklet Breast prostheses, bras and clothes after surgery.

You may also find it helpful to read Macmillan Cancer Support’s booklet Understanding risk-reducing breast surgery (see page 35).

Ǫuestions to ask your breast surgeon

Make sure you have all the information you need before deciding about surgery.

You may find it helpful to write down any questions and to take notes during your appointments.

Taking someone with you can help you remember what has been discussed and give you extra support.

You may want to ask your surgeon:

- Which reconstruction options would be suitable for me and why?

- What are the benefits, limitations and risks of this type of surgery?

- Would I be able to keep my nipples?

- When would I be able to have my surgery done?

- How long would I have to stay in hospital?

- What is the recovery time for this operation?

- When would I be able to move about, walk, drive and exercise?

- How much pain is there likely to be?

- Would I need to wear a special bra after the operation?

- Can you show me where the scars would be on my body and how big they would be?

- Can you show me any photographs or images of your previous breast reconstructions?

Discussing your operation with your breast surgeon before deciding is important. They’ll want to make sure you fully understand the process and, if you’re having reconstruction, have realistic expectations of how your reconstructed breasts will look and feel.

Timing of your surgery

When the right time is to have risk-reducing surgery is an individual decision.

There are many things to consider, such as:

- Your age

- The age at which any family members were diagnosed with cancer

- How anxious you feel about your cancer risk

- Whether you’re considering having children and if breastfeeding is important to you

- If you have children, their ages and possible childcare requirements while you recover

- Important life events such as your education or career

- Any existing health conditions you have

It’s important to take as much time as you need to make the right decision for you.

Changes to your body after risk-reducing surgery

Adjusting to how your breasts and body look after surgery can be difficult. Getting used to physical changes such as scars and loss of sensation can take time.

Breast reconstruction can only reconstruct a breast shape. It can’t bring back your breasts or the sensations of the breast and nipple.

Talking to your breast team and asking for photographs of their work can help prepare you for what to expect after your operation.

Talking to someone who has had a similar experience can also be helpful. Our Someone Like Me service can arrange for a volunteer to talk to you by email or phone (see page 34).

Surgery to remove both ovaries and fallopian tubes

Women with an altered BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene are also at higher risk of developing ovarian cancer.

Ovarian cancer risk starts to increase significantly from the age of 40 for BRCA1 gene carriers and from the age of 45 for BRCA2 gene carriers.

For pre-menopausal women who are BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene carriers, having surgery to remove the ovaries and fallopian tubes has been shown to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer by up to 90–95%.

This type of surgery is known as a risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (RRBSO).

For pre-menopausal women who carry the altered BRCA2 gene, some studies suggest having an RRBSO may also reduce the risk of breast cancer.

Your genetics team can explain more about the risks and benefits of the surgery.

Deciding whether to have surgery

You’ll see a gynaecologist who can advise you on when you may want to consider risk-reducing surgery to the ovaries and fallopian tubes.

Deciding whether or when to have an RRBSO is a very personal decision.

Things to consider will include:

- Your age

- If you want to have children or add to your existing family

- Whether you are a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene carrier

The womb is not usually removed as part of an RRBSO. However, If you have any other benign (not cancer) womb conditions, your specialist team may also discuss removing the womb at the same time as your ovaries and fallopian tubes.

This is known as a total hysterectomy.

Ongoing research is looking at doing this surgery in two stages. The fallopian tubes are removed first, and the ovaries are removed at a later date The benefit of

this approach is that it delays the onset of menopausal symptoms. This surgery is currently only offered in the UK as part of a clinical trial called the PROTECTOR trial. Your specialist team will let you know if this is offered at your hospital and if you’re eligible for this trial.

Managing menopausal symptoms after surgery

If you’re pre-menopausal, having an RRBSO will cause an early menopause. You’ll stop having periods and you’ll no longer be able to get pregnant.

For some women, menopausal symptoms can be severe and have a significant impact on quality of life.

Symptoms include:

- Hot flushes and night sweats

- Vaginal dryness

- Changes to sex drive

- Weight gain

- Mood changes

If you’re under 50 and have not had breast cancer, your specialist team will discuss the option of taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to help with menopausal symptoms.

If you have had breast cancer, taking HRT after an RRBSO is not usually recommended. However, if your symptoms are affecting your everyday life and you have tried non-hormonal ways to manage them, your treatment team may discuss the risks and benefits of taking HRT in individual cases.

Our Menopausal symptoms and breast cancer booklet includes ways to help manage menopausal symptoms.

Bone health

An early menopause can increase your risk of developing osteoporosis in future. Osteoporosis is a condition where your bones lose their strength and become fragile and more likely to break.

If your specialist team is concerned about your risk of osteoporosis, they may suggest a DEXA scan at the time of surgery to check your bone health. Follow-up DEXA scans may also be recommended in the future.

You can find more information on bone health and osteoporosis on the Royal Osteoporosis Society website theros.org.uk

Oral contraceptive pill and cancer risk

Evidence has shown that taking the oral contraceptive pill can protect women from developing ovarian cancer, and the longer you take it the greater the benefit.

However, it may also slightly increase the risk of developing breast cancer.

Taking the pill may slightly increase or decrease your risk of some other cancers too.

There are no guidelines that recommend taking the pill to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer and your genetics team can discuss this with you.

TALKING TO YOUR FAMILY

If you have an altered gene or your family history puts you at an increased risk, this will mean other members of your family may also be at an increased risk.

Talking to your family means they can make choices about assessing and managing their own risk.

Talking to family after a positive genetic result

If you have tested positive for an altered gene, it’s important to talk to your family about your result.

First-degree relatives (such as brothers, sisters, children and future children) will have a 50% chance of also being a gene carrier.

You may feel worried or guilty about telling family members that they may be at increased risk of developing cancer.

Your genetics team can support you. They should provide you with prepared letters you can give to your relatives. The letter will suggest they see their GP to discuss the possibility of a referral to a genetics centre.

You may feel it would be better to tell your relatives face to face, or you may prefer to phone or email them. This may be difficult if family relationships are strained or have broken down.

How family members may react

Their reactions may vary.

It may come as a shock to them. Some relatives may ignore the result and may even find it difficult to talk about.

Others will be glad you told them about the possibility they may be a gene carrier and will want to have a genetic test themselves.

Remember no one is to blame for the genes they inherit or pass on. Telling family members they may be a gene carrier will give them the option to discuss genetic testing and manage their own risk.

Talking to children

The thought of talking to your children about your genetics results may be difficult. You may also feel that by not telling your children, you are protecting them.

There are no set rules, and it will depend on their age and character.

Younger children may only need a small amount of information, whereas teenagers may want to know more and have lots

of questions.

You may be a family that talks openly about everything or you may come from a background or culture where intimate or serious issues are not talked about, or are kept between adults.

You may talk more easily to one of your children than to another.

What you decide to tell your children will depend on a number of different things. But being open and honest and talking to your children as soon as you feel ready can be helpful for you both.

Tips for talking to children

- Children and teenagers usually respond better to informal conversations, often while you’re doing things together

- Give them small amounts of information at a time to help them understand at a pace that’s right for them

- Ask them to say in their own words what they think is happening so you can see if they’re confused about anything

- Reassure them they can ask you anything, and if they do ask a question make sure you have understood why they are asking it

- Include positive messages about what can be done now you know you have an altered gene, that you have choices to reduce your risk and that having an altered gene does not mean you’ll definitely develop cancer

- Let them know children and young people are not at risk and they have just as much chance of not inheriting the gene

Keep talking with your children regularly about what’s happening so they feel involved, informed and able to ask any questions. You may need to repeat explanations, especially to younger children.

WORRIES ABOUT PASSING ON AN ALTERED GENE IN THE FUTURE

If you or your partner is a gene carrier, any children you have will have a 50% chance of inheriting the altered gene.

Your genetics team can talk through options you may want to consider when planning a family.

While some people look at ways to avoid passing on the gene, many people choose to have children without any intervention.

Some people decide not to have a family while others consider adoption.

Deciding what to do can be difficult and emotional.

Your genetics team can give you information and support, and can refer you to specialist fertility services if you’re eligible to talk through your options.

Looking for an altered gene when you’re pregnant

You may choose to get pregnant naturally and have pre-natal testing.

This involves taking a sample of tissue from the placenta or the fluid that surrounds the baby in the womb to see if your baby has inherited the altered gene.

You can then decide whether to continue with the pregnancy.

This procedure may not be routinely offered and your genetics team can talk to you about your options.

Avoiding passing on an altered gene

Pre-implantation genetic diagnosis

You may want to talk to your genetics team about pre- implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD).

PGD involves going through an in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) cycle, where an egg is removed from the ovaries and fertilised with sperm in a laboratory.

The fertilised egg (embryo) can be checked for the known altered gene.

Only embryos that do not carry the altered breast cancer gene will be transferred to the womb.

PGD is not available to everyone on the NHS and is currently only offered in a few hospitals in the UK.

Genetic Alliance UK and Guy’s and St Thomas’ PGD centre (see page 36) have more information about pre-implantation genetic diagnosis.

Egg or sperm donation

Depending on which parent has the altered gene, you may want to consider using donated eggs or sperm to avoid passing on the altered gene.

The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (see page 36) has information about egg and sperm donation.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Clinical trials

Clinical trials are being carried out to find out more about genes and breast cancer. You may be offered the chance to take part in one of these trials.

You can search for clinical trials on the Cancer Research UK or Be Part of Research websites (see page 36).

Insurance and genetic testing

If you have had a test to see if you have the same altered gene as a family member (predictive genetic test), you do not have to disclose the result when you apply for insurance, such as life or health insurance (under a certain amount).

However, insurance companies do ask about your family’s medical history. If you have a significant family history of breast cancer you may be charged a higher premium.

If you have been diagnosed with breast cancer, you’ll have to disclose this and it may be more difficult to get travel insurance.

Genetic Alliance UK and the Association of British Insurers (see page 37) have information on insurance and genetic conditions on their websites.

Changes to the breast or chest area

Whatever your level of risk, and even after risk-reducing breast surgery, it’s important to look and feel for changes to your breast or chest area so you know what’s normal for you.

Contact your GP or breast team as soon as possible if you notice any changes that are unusual for you. The sooner breast cancer is diagnosed, the more successful treatment is likely to be.

You can find out more about changes to look and feel for in our booklet Know your breasts: a guide to breast awareness and screening.

For more information on staying breast and body aware after breast cancer treatment, see our booklet After breast cancer treatment: what now?

FURTHER SUPPORT

Breast Cancer Now

If you have had genetic testing, been identified as a gene carrier or have any concerns about breast cancer in your family, you can call our Helpline on 0808 800 6000.

Alternatively you can contact us using the Ask Our Nurses email service.

Our Someone Like Me service can put you in touch with a trained volunteer who has had experience of the issues you’re facing. Talking privately over the phone, where and when it suits you, means you can ask any questions you like and talk openly without worrying about the feelings of the person listening.

Some of our volunteers can also chat by email.

To find out more about any of our services, visit breastcancernow.org or call our Helpline on 0808 800 6000.

Useful organisations

Family history, cancer risk and altered genes

BRCA Link Northern Ireland – brcani.co.uk

Based in Northern Ireland, helping BRCA gene carriers access information and support.

BRCA Chat – brcachat.com

Charity that aims to help anyone navigating a BRCA (or other) gene mutation.

FORCE (Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered) – facingourrisk.org

For individuals and families with an altered gene or at high risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Based in the USA but has a UK support network.

Genetic Alliance UK – geneticalliance.org.uk

Works to improve the lives of patients and families affected by all types of genetic conditions.

Macmillan Cancer Support – macmillan.org.uk

Provides information about family history, genetics and cancer risk. Also publishes a booklet called Understanding risk- reducing breast surgery.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence – nice.org.uk/guidance/cg164/resources

Decision aids for women considering drug treatment to reduce their risk of developing breast cancer.

PALB2 interest group – palb2.org

Arranges information sessions for people who have an altered PALB2 gene.

Royal Marsden NHS foundation trust – royalmarsden.nhs.uk

Publishes a booklet called A beginners guide to BRCA1 and BRCA2, also available online.

Ovarian cancer

Eve appeal – eveappeal.org.uk

Funds research and raises awareness of gynaecological cancers, including ovarian cancer, and has information on inherited risk.

Ovacome – ovacome.org.uk

Support and information for women affected by ovarian cancer, their families and friends.

Ovarian Cancer Action – ovarian.org.uk

Provides information and support to women with ovarian cancer.

Breast reconstruction

Keeping abreast – keepingabreast.org.uk

Provides information, support, practical help and advice for those considering breast reconstruction, including the opportunity to share the experiences of others.

Restore: Breast Cancer Reconstruction Support – restore-bcr.co.uk

Information and support around breast reconstruction.

Fertility issues

Guy’s and St Thomas’ Centre for PGD

– guysandstthomas.nhs.uk/our-services/pgd

Expert information on fertility and pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD).

Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority – hfea.gov.uk Provides information about IVF and fertility treatments

in the UK.

Clinical trials

Be Part of Research – bepartofresearch.nihr.ac.uk

Find out about health research that’s taking place across the UK.

Cancer Research UK

– cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/find-a-clinical-trial Search for clinical trials.

Osteoporosis

Royal Osteoporosis Society – theros.org.uk

Dedicated to improving the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis.

Menopause and menopausal symptoms

Daisy Network – daisynetwork.org

Support group for women who experience premature menopause.

Menopause Matters – menopausematters.co.uk

Information about the menopause, menopausal symptoms and treatment options.

Women’s Health Concern

– womens-health-concern.org

WHC is the patient arm of the British Menopause Society (BMS).

Insurance

Association of British Insurers (ABI) – abi.org.uk Information on genetic testing and insurance.

HELP US TO HELP OTHERS

Breast Cancer Now is a charity that relies on voluntary donations and gifts in wills. If you have found this information helpful, please visit breastcancernow.org/give to support our vital care and research work.

ABOUT THIS BOOKLET

Family history of breast cancer: managing your risk was written by Breast Cancer Now’s clinical

specialists, and reviewed by healthcare professionals and people affected by breast cancer.

For a full list of the sources we used to research it: Email health-info@breastcancernow.org

You can order or download more copies from breastcancernow.org/publications

We welcome your feedback on this publication: health-info@breastcancernow.org

For a large print, Braille or audio CD version: Email health-info@breastcancernow.org

At Breast Cancer Now we’re powered by our life-changing care. Our breast care nurses, expertly trained staff and volunteers, and award-winning information make sure anyone diagnosed with breast cancer can get the support they need to help them to live well with the physical and emotional impact of the disease.

We’re here for anyone affected by breast cancer. And we always will be.For breast cancer care, support and information, call us free on 0808 800 6000 or visit breastcancernow.org

Breast Cancer Now

Fifth Floor, Ibex House, 42–47 Minories, London EC3N 1DY

Breast Cancer Now is a company limited by guarantee registered in England (9347608) and a charity registered in England and Wales (1160558), Scotland (SC045584) and Isle of Man (1200). Registered Office: Fifth Floor, Ibex House, 42–47 Minories, London EC3N 1DY.

Lahore Clinic

- 0324 9780880

- info@drahsanrao.com

- One-stop Clinic (surgical-review,breast ultrasound scan and mammogram, biopsy all in same clinic)

- Shaukat Khanum Hospital Rd, Block R3 Block R 3 Phase 2 Johar Town, Lahore, 54000

Timings

- Assistant : Adeel

- 0324 9780880

- Timings: Tuesday (9 AM to 5 PM) Wednesday (2 PM to 6 PM) Telephonic:(6 PM to 8 PM)

- Copyright © 2024 Dr. Ahsan Rao All rights reserved.